Abstract

The US Small Business Administration (SBA) exclusively selected ControlPoints to spearhead their implementation of DHS’ Continuous Diagnostics & Mitigation (CDM) cybersecurity program. Our leadership yielded the SBA $1.6M in savings by transforming their CDM program into the federal government’s first deployment in the cloud, which also served as a successful test case for the whole of the US government. In a subsequent FITARA scorecard, the SBA stood out as one of just a few agencies that received an ‘A’ for their implementation of the

Modernizing Government Technology Act – primarily due to this CDM deployment. In this case study, we share the efficiencies gained going to the cloud, our key lessons learned from the ground floor, a few noteworthy challenges and insights for improving the program.

CDM Overview

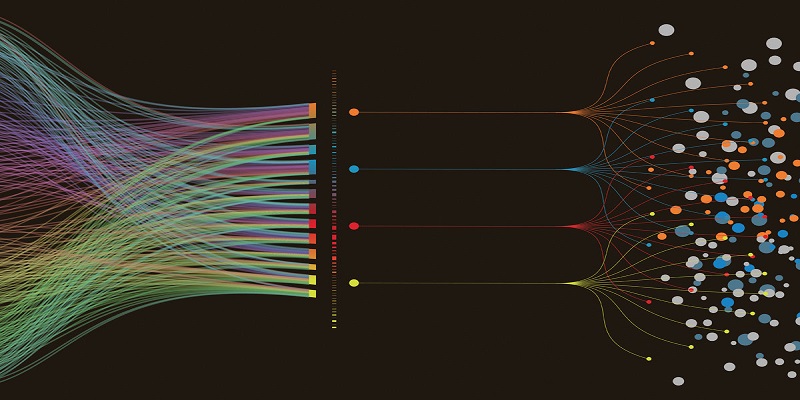

The CDM program is a government-wide initiative of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to provide commercial off the shelf tools (COTS) to agencies for deeper visibility into their networks and to identify real-time attacks across the federal government. The program is designed to transform agencies from manual, compliance-based and checklist driven processes to automated, risk-based data collection activities that occur in near real-time.

There are four phases currently that organize the CDM program:

The combination of these phases, which continue to evolve with the changing dynamic of threats and technical advancements, are intended to improve IT operations, cyber hygiene, and enterprise risk management.

Gap Analysis

Two year prior to ControlPoints overseeing the program, DHS performed a cursory review of the agency’s cyber capabilities and established a baseline of tools and licenses that would be required. At the time ControlPoints took helm of the multimillion-dollar project, DHS’ implementation was planned to begin within one month. In other words, prior to the implementation kickoff all agency responsibilities had to be completed.

Within days however, we recognized there were significant issues and unfinished tasks. For starters, we noted the scope was incomplete because only a portion of the agency network had been considered in the original design. We found key offices were either not apprised of the forthcoming deployment or unaware of the initiative altogether. We also discovered the area of the network that was included in the original scope had subsequently undergone major changes, thus necessitating a re-baselining to reflect the current IT environment. A complete and accurate scope for a major IT project is key to avoid time and effort implementing a partial solution, duplicating technologies or encountering procurement delays due to the close of the budget cycle.

Given the substantial visibility for the success (or failure) of the initiative to external stakeholders and senior leadership we quickly developed a project risk register to inventory every issue by priority with actionable recommendations to mitigate each entry. We presented an executive summary to the Board, CIO, CISO, CFO, OIG and other participants. Upon formal acceptance for our proposed course of action, we negotiated a new implementation start date with DHS. Having quickly grasped the key issues and taken full ownership for the program’s outcome, DHS’ confidence was reinforced seeing that the agency was not only committed to the initiative in a serious manner but that it intended to rollout the program successfully.

As we began re-scoping the full agency network and engaging key program offices we realized there was a mixture of cyber tools utilized across the agency, some redundant and some incompatible with the CDM architecture. Among the redundant tools, some either did not meet the minimum version required or lacked sufficient licenses. To get a clear handle we performed a gap analysis of existing technologies against the CDM tools baseline with the objective of leveraging as much of the in-house technology as possible. Our detailed analysis captured current license counts, costs to obtain sufficient licenses, length of existing vendor contracts, and costs to train and maintain support personnel. This analysis effectively drove intelligent budgetary decisions because it shed light on precisely what additional expenses would be needed, for what purpose and by which dates.

Cloud

Let us take a moment to define “cloud” in the context of this case study. Cloud is the on-demand availability of computing resources over the Internet Companies employ cloud services because it allows some or all of their IT to be managed by a vendor, it only charges on a pay-per-use basis, and provides the ability to scale immediately as business needs change.

Infrastructure-as-a-service (IaaS) is the most basic category of cloud computing, which is where a customer rents foundational IT infrastructure from a cloud provider. IaaS typically includes servers and virtual machines (VMs), storage, network and operating systems.

Azure is an example of a public cloud because it is owned and operated by an independent provider (Microsoft). A customer simply uses a web browser to access their service on Azure and manage their account.

Cloud services enable resources to be allocated, consumed and de-allocated on the fly to meet peak demands. Just about any system is going to have times when more resources are required and when that surge in demand occurs, a cloud environment allows compute, storage and network resources to scale instantly.

Hybrid cloud is the combined usage of on-premises (traditional IT in a data center) and off-premises (in the cloud) IT environments. However, combining conventional legacy and virtualized systems hosted in on-premises and off-premises environments, respectively, can be an integration challenge, not just to get the two systems to interact effectively, but also to achieve the situational awareness required in both environments.

Drive Transformation

CDM was thoughtfully designed to be an on-premises solution; requiring physical server rack space in a data center to house its tools. However, we determined the agency lacked sufficient physical space to store the new CDM equipment due to inefficient space utilization, restrictive contracts and budget limits.

Coincidentally, the agency had already begun designing a data center consolidation solution to comply with the Federal Data Center Consolidation Initiative (FDCCI). This is a requirement of the Federal Information Technology Acquisition Reform Act (FITARA) and OMB Memorandum M-16-19, whereby agencies must transition to more efficient infrastructure such as cloud services and inter-agency shared services. In an effort to capture economies of scale between the parallel yet separate Data Center and CDM initiatives, we helped drive the decision to host CDM in the forthcoming cloud environment for the Data Center. This not only solved the physical space constraint issue but also combined two distinct initiatives to create synergy and lower total cost.

Given CDM was not conceived to be hosted on a cloud platform, to ensure success of this first of a kind venture we held numerous design meetings with agency personnel, DHS, Microsoft and COTS tool vendors in order to architect an optimal solution. Discussions centered on establishing dedicated network security zones and virtual private networks (VPN) on an IaaS public cloud in a hybrid IT model, developing naming conventions, optimizing VM configuration (CPU, memory, storage, load balancing), effectively managing IP addresses/routing/switching/certificates, and establishing access permissions. Another key component of the architecture design contemplated mitigating latency issues with data travelling between agency sites, telecommunications providers, redundant cloud locations, and within the cloud itself.

Drive Efficiencies

Among the attractive benefits of cloud is that native security tools oftentimes comprise the overall solution and third party tools can be integrated at lower cost. Henceforth, we engaged Microsoft to co-develop a roadmap of existing and forthcoming cloud security tools, including a timeline of key functionality maturing, to plan our short and long-term adoption strategy in order to drive down future CDM program costs. This is significant because agencies will eventually need to self-fund their CDM programs. Taking a strategic approach to lowering future costs also helped make the case for a federated adoption of CDM.

It is also worth mentioning that making use of native cloud tools reduces the overall IT footprint and time to mitigate vulnerabilities. A greater centralization of technologies within a cloud platform means there are less tools that require patching by the customer. In addition, cloud platforms require more up to date versions and configurations of the applications and tools hosted onto them, hence maximizing automated updates. Minimizing legacy technology that carry outdated versions and configurations helps to accelerate modernization, lower total maintenance costs, and enhance security and compliance.

Our Keys to Success

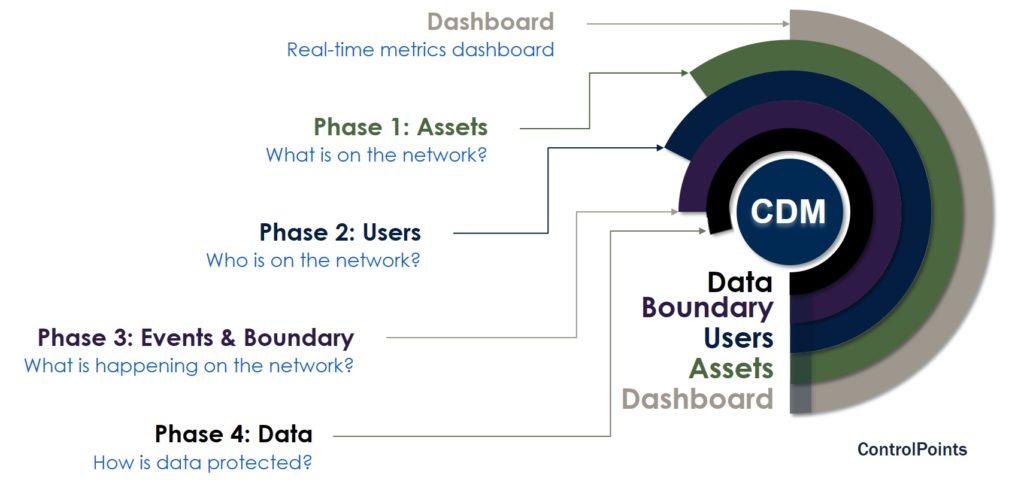

Drive Culture Change: Generally, major investments designed to transform operations will invite a healthy dose of skepticism and hesitation. For deeply private agencies not accustomed to sharing data with outside entities, let alone real-time network threat intel (even if intra-agency), CDM elevates cynicism even more so. One of the keys to achieving change is clearly establishing the reasons necessitating the change itself and then focusing messaging around it. To help foster the cultural shift necessary to fast track adoption, we developed the illustration below to simplify the federal mandate as it evolved and how it connected directly to the agency. We continued to revisit it to help key participants rationalize the initiative.

Mature Governance: Connecting the mission to the federal mandate and program objectives, and making the business case to key participants combined with our deep cyber risk thought leadership quickly lowered resistance to the effort. Cataloging all project risks promptly, recommending viable deployment options, continuously intaking feedback and providing rigorous project management contributed to shortening the delivery time of the deployment.

Disruptive Innovation: This was the first CDM deployment in the cloud for any federal agency and our project success has since prompted DHS to architect future CDM solutions for cloud platforms. The project spanned the entire IT transformation effort, including large-scale data center consolidation and virtualization of both IT shared services and legacy applications. Right from the start our approach was innovation-, risk-, cost-, time-, and quality-centric, which helped drive the decision to consolidate two distinct initiatives.

Uncompromising Quality: Our rigorous project management approach ensured all inputs and variables were evaluated with a critical eye. We took the time to understand the agency’s mission, define key roles & responsibilities, frequently communicate project goals and desired outcomes, measure milestones with meticulous attention to detail, validate architectural decisions, convey technical aptitude, foster a collaborative environment, facilitate open and forthright communication, provide training, escalate critical issues timely, empower team members and capture feedback for continuous improvement. We coordinated the activities of over 70 federal and contractor personnel, in addition to internal Program Offices that resulted in a successful and expectations-surpassing deployment of 9 months and a net positive cyber ROI. Our core expertise in technology and cyber risk management was crucial in gaining consensus with technology leaders in a dynamically changing environment.

Make an Impact: According to Ms. Maria Roat, SBA’s CIO (subsequently US Deputy Federal CIO), “when CDM was rolled out it was very focused on the tools but not necessarily on the outcomes and the intent of CDM. I had 40 tools [before CDM] — I got rid of those, and I’m down to about 10 right now.” Moreover, CDM now allows the agency to stay “predictive” about activities on the network. “Being able to see our entire inventory, who’s on our network, what they’re doing, how they’re using our networks, and having visibility into that environment – that’s something we did not have before.” In the most recent FITARA scorecard, the SBA stood out as one of just a few agencies that received an ‘A’ for their implementation of the Modernizing Government Technology Act.

ControlPoints takes pride in having helped our federal customer innovate while at the same time advancing and enhancing a critical national security initiative.

Future CDM Considerations

The Report to the President on Federal IT Modernization, describes the challenges faced in trying to combine existing cyber defenses with new cloud and mobile architectures. DHS’s National Cybersecurity Protection System (NCPS), which includes both the EINSTEIN cyber sensors and a range of cyber analytic tools and protection technologies, provide value but are not enough to combat the full spectrum of advanced persistent threats that rapidly change the attack vectors, tactics, techniques and procedures.

Moreover, DHS has begun a cybersecurity architectural review of federal systems, building on a similar Defense Department effort by the Defense Information Systems Agency, which conducted the NIPRNET/SIPRNET Cybersecurity Architecture Review (NSCSAR) in 2016 and 2017. Like NSCSAR, the new .Gov Cybersecurity Architecture Review (.GovCAR) intends to take an adversary’s-eye-view of federal networks in order to identify and fix exploitable weaknesses in the overall architecture. Lesson learned there indicate CDM will require nimbleness to keep adapting to continued advancements by threat adversaries.

In addition, CDM is a centrally funded but locally deployed system, where technology varies from agency to agency and implementation to implementation. The government’s network perimeter is no longer a contiguous line. Cloud-based systems are still part of the network, but the security architecture may be completely different, with complex encryption that presents challenges to CDM monitoring technologies almost as effectively as it blocks adversaries. For example, some sensors on a network may not be able to decipher encrypted data if it is in the wrong format (in other words no value would be returned), thereby limiting visibility in the cloud.

Finally, with increasing cloud adoption effective configuration of the cloud becomes imperative. Unsecured cloud configurations can leave back doors wide open for adversaries to view sensitive data. Agencies will need to lock down rights management, data loss prevention, and consider micro segmentation to ensure any compromises stay isolated.