In December 2020, Texas-based IT firm SolarWinds revealed it was infiltrated by highly sophisticated actors who laced malware into a core infrastructure product, called Orion. Over 18,000 customers around the globe received tainted updates of the product, which opened a gateway and a foothold into the networks of unsuspecting Fortune 500 and governments. The campaign prompted the US Pentagon to order an emergency shut down of their classified SIPRNET system and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) to instruct every federal agency immediately disconnect any computer running Orion.

The firm’s CEO previously boasted in an October 2020 analyst call, “there was not a database or an IT deployment model out there to which [we] did not provide some level of monitoring or management. We manage everyone’s network gear.” This deep market penetration elevated the company into a prized target for a supply-chain attack, where an attacker exploits the less rigorous security of a niche vendor so that it can subsequently weaponize the supplier for a pivot attack onto their larger customer base, where there is lucrative digital gold (high value data) to be gained.

The sophistication and scale of this audacious attack is an inflection point for governments, organizations and security defenders worldwide. This post identifies the root causes and recommends unique technical and regulatory countermeasures.

Exploiting Supply Chain Blind Spots

Examples of past supply-chain attacks include a casino breached through a fish tank that was connected to the internet, Ticketmaster having its JavaScript in third-party payment forms compromised that then send credit card data to criminal groups, and a Managed Security Provider’s (MSP) remote access tool compromised to launch ransomware attacks on 22 Texas towns.

In a supply-chain attack, the ultimate target is not the first victim but rather the higher value data of the customer base of the vendor. This pivot attack offers two advantages: 1) attackers can avoid a potentially higher security standard of the secondary victim and 2) the attack scales easily – as in the case of SolarWinds’ 18K globally impacted customers.

SolarWinds became an ideal candidate for discovering the daily ins and outs of citizens in a sovereign nation as well as ascertaining top-tier secrets of government because its software is utilized across numerous industries like law, healthcare, banking, and government. It turned even more attractive after outsourcing ongoing development of their products (which included Orion) to Eastern Europe, where labor costs and regulation standards are low and cyber-crime is traditionally higher. None of the SolarWinds customers contacted by The New York Times was aware they were reliant on software that was maintained in Eastern Europe.

Further exasperating the supply chain blind spot, some companies may not even know that they utilize SolarWinds’ Orion services. For example, in the critical infrastructure operational technology (OT) space (e.g., transportation control systems, power plants, water management, etc.), SolarWinds is commonly bolted into industrial control systems (ICS) by original equipment manufacturers (OEMs). On the other hand, some critical infrastructure personnel outsource maintenance and support to a vendor who may be utilizing a white-labeled security product that consists of SolarWinds (to make a remote connection into the ICS network).

Enterprise Governance Weaknesses

A former cybersecurity advisor to SolarWinds warned in 2017 of a likely ‘catastrophic’ hacking attack if the company did not significantly improve internal security measures. He advised executives to install a cybersecurity senior director.

Yet, the company didn’t hire its first Chief Information Officer (CIO) or VP of “security architecture” until it was threatened with penalty under a European privacy law. That law became relevant because much of the engineering function was moved to satellite offices in the Czech Republic, Poland and Belarus, where engineers had access to the Orion network management software that was eventually misconfigured. The company still does not have a Chief Information Security Officer (CISO).

SolarWinds’ CEO of 11 years was a trained accountant and a cost-saving expert as its former Chief Financial Officer (CFO). Former and current SolarWinds staffers say the company was slow to prioritize security, even when top cybersecurity companies and federal agencies adopted its software. This was embodied in the days after the attack became public when it was discovered the compromised Orion code was still available for download on SolarWinds’ website.

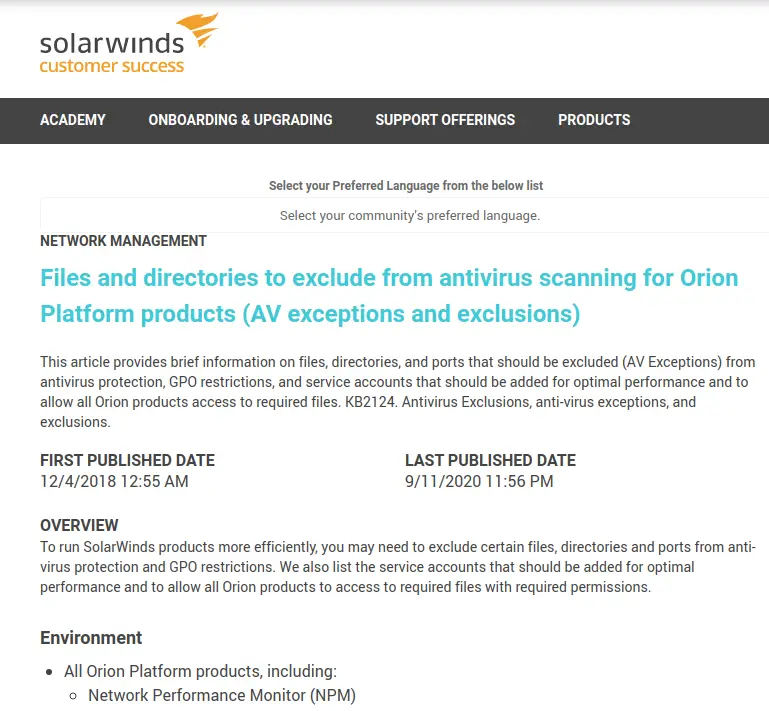

In another example of lax security, a SolarWinds support page (now removed) advised users to disable anti-virus (AV) scanning for certain Orion product folders “to prevent possible application related issues, unexpected behavior and performance related problems.” Note: the purpose of AV is to detect and protect from exploited code and misconfigurations.

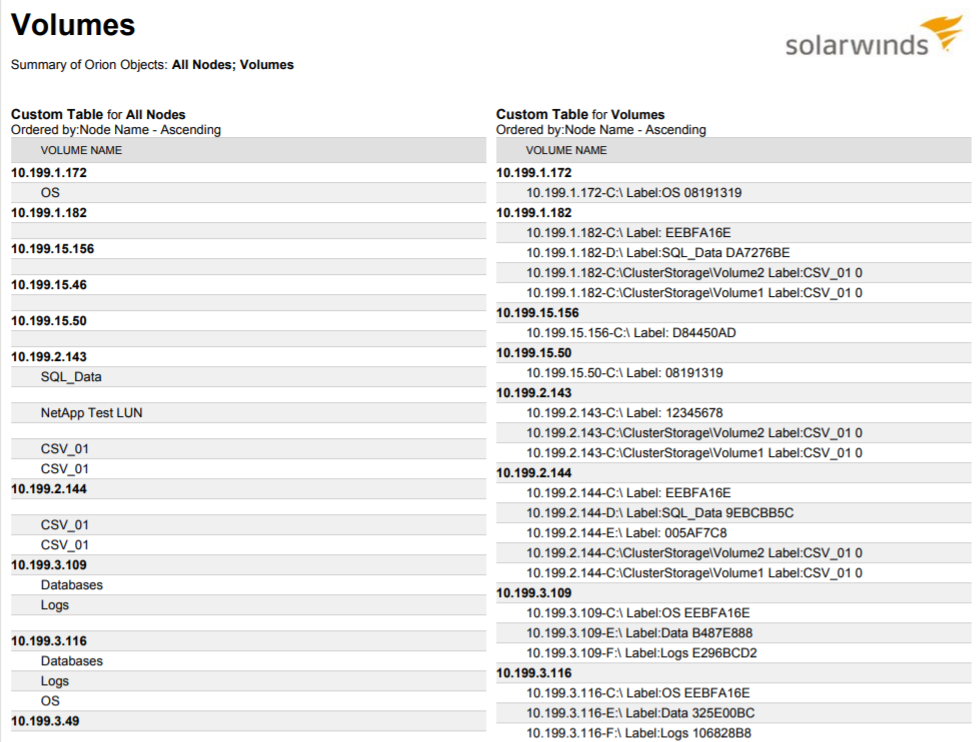

Image Source: @craiu

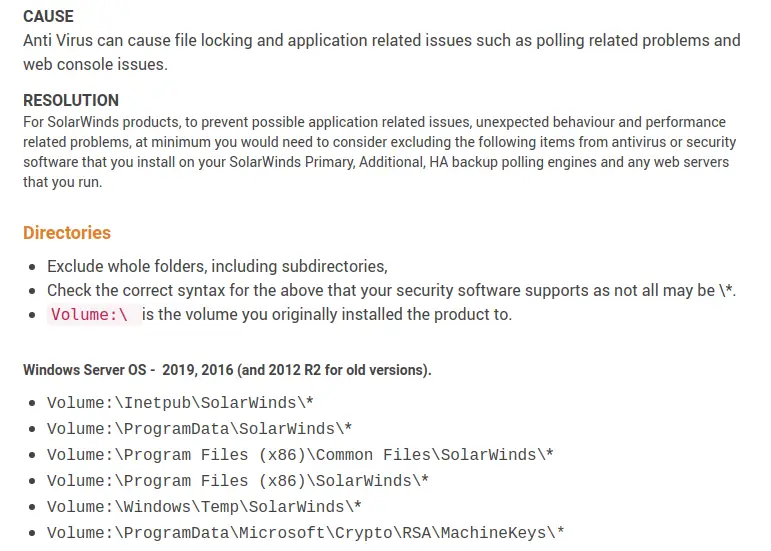

The SolarWinds network may have been carefully mapped by the sophisticated actors even before touching the codebase. Proprietary intel information about SolarWinds and its customers is on display for anyone with an internet connection: https://thwack.solarwinds.com. In one forum post, a SolarWinds engineer responded to a 2017 support query offering the layout of the cork.lab lab environment on the internal network.

Image Source: thwack.solarwinds.com

A list of all nodes and table volumes for Orion objects is still readily available.

Image Source: https://thwack.solarwinds.com/xcdhs76427/attachments/xcdhs76427/sam-discussions/30440/1/Volumes.pdf

Finally, in 2019 a researcher came across an internal update server that was accessible on the Internet with the password “solarwinds123”.

Ownership Structure

In PwC’s 2020 Annual Corporate Directors’ Survey, two-thirds of respondents agreed that a cyber-breach would reflect poorly on their board. At the audit committee level, KPMG’s most recent biannual Audit Committee Pulse Report ranked cyber risk atop corporate risk agendas.

Yet, in the aftermath of the highly sophisticated attack, we have learned SolarWinds consistently made decisions that undermined foundational security hygiene. While the organization certainly appeared to skimp on basic cyber investments, the underlying factor may be due to how the business is structured.

SolarWinds was founded in 1999, issued an IPO in 2009 and was organically growing through business acquisitions that added to its product portfolio. In 2015, private equity (PE) investment firms Silver Lake Partners and Thoma Bravo acquired SolarWinds. They financed the purchase with SolarWinds’ own $2 billion of debt. In other words, SolarWinds raised capital (possibly to pay off outstanding loans) by issuing company bonds at a discounted price, which the PE firms bought, rendering them majority owners. In 2016, the PE firms took SolarWinds private and sped up acquisitions before completing a new public offering in 2018, rebranding SolarWinds from a network monitoring company to a cybersecurity provider.

The typical goal of PE firms is to acquire established businesses then actively manage growth and internal efficiencies to provide the investors with profit (within a 4 to 7 year window), eventually leading to an exit.

Some private equity firms, however, have a reputation of raising and/or borrowing large amounts of money to target firms they believe have market power then employing a strategy to raise prices, cut head count, outsource/offshore to cheaper labor markets, sell assets, take advantage of legal loopholes, or collect insurance money via a bankruptcy. For example, Toys R’ Us, Payless Shoes, and RadioShack were all acquired by PE firms and are now either in bankruptcy or worth significantly less.

PE firms are largely comprised of attorneys and accountants and their in-house expertise lies in analyzing financials, identifying undervalued companies and structuring legal arrangements to purchase, improve and sell companies. They drive growth by prioritizing budgets first for sales / marketing / acquisitions, then development / engineering, and then infrastructure support. Cybersecurity is not among the typical PE company’s core competencies, or priorities.

For profit-focused financiers, functions like cybersecurity are perceived to be nice to have but are not essential to “keep the lights on”. PE-owned SolarWinds appeared to follow this path, streamlining internal operations at the expense of cyber investments barely hanging by a thread.

A few prominent cybersecurity companies owned by PE firms:

- RSA Security (acquisition of Symphony Technology Group)

- Symantec (acquisition of Ireland-based Accenture)

- Forcepoint (acquisition of Vista Equity)

- SailPoint, DigiCert, Bluecoat (acquisitions of Thoma Bravo)

- Rapid7, ObserveIT (acquisition of Bain Capital)

- CoalFire, Fortinet (acquisitions of The Carlyle Group)

Note: this list excludes companies that were born out of venture capital (VC), like CrowdStrike, Tanium, and Cloudflare. VC firms may also adopt ROI-driven priorities.

As PE firms eye companies in the cybersecurity space, not all are possibly looking to scale, transform, turn around, and speed up growth to make them work better for a future sale or IPO. If investor objective is short-term gains over long-term value creation, this elevates risk beyond the company because many cyber firms offer products that not only protect businesses in the general economy but also critical infrastructure with national security implications, as in the case of Orion.

Although SolarWinds’ annual profit margins nearly tripled from 2010 to 2019 ($152 million to $453 million, respectively), risk to its customer base force multiplied in the process. FireEye had its proprietary defense tools stolen, Microsoft had its source code revealed (for possible future attacks), and sensitive data of the FBI, Treasury, DHS, DoD and many others exposed.

In short, PE acquisitions of cybersecurity firms can pose a national security risk if the primary objective of the deal isn’t aligned to improve cybersecurity but rather profits. Given PE firms, especially foreign-based, retain their prerogative to install favorable board members and deprioritize audit committee and cyber accountability recommendations, deeper mergers & acquisition (M&A) regulatory oversight is necessary before authorizing a PE-backed cyber acquisition.

Nation-State Attribution

FireEye was the first to detect the Sunburst malware but before the news of it was publicly disclosed, its CEO received a mysterious postcard at his home that carried a FireEye logo and contained a cartoon mocking any claims that Russia might have been behind the attack, with the text “Hey look Russians” and “Putin did it!”

Image source: mypostcard

The question of who may have carried out this attack is not easy to answer because the digital forensic industry requires further maturing. It could be Russia, or it could be China, or the Five-Eyes, or the CIA/MI-6/Mossad, or even companies intimately pervasive within homes and businesses – Microsoft or anti-virus vendors.

With the exception of sloppy practices, an attacker typically would not leave any evidence in their code that could point back to them. Some nations however, are incentivized to manipulate pieces of clues to appear to link their adversaries as the source. For example, attackers have used tools in the past that allowed them to “spoof” their malware code to look like it was created from another language. While two sets of distinct attackers may use similar coding languages, logic or even philosophy – that is insufficient to attribute the source of an attack upon one actor over another actor. Nevertheless, even with this limitation we can narrow the suspect list based on historical indicators and reading into possible motives.

In general, criminal hackers focus on near-term financial gain. They use techniques like ransomware to extort money from their victims, steal financial information and harvest computing resources for activities like sending spam emails or mining for cryptocurrency.

Criminal hackers exploit well-known vulnerabilities that, had the victims been more thorough in their security, could have been prevented. Attackers typically target organizations with weaker security, like health care systems, universities and municipal governments.

Attackers associated with national governments, on the other hand, have entirely different motives. They look for long-term access to critical infrastructure, gather intelligence and develop the means to disable certain industries. They also steal intellectual property — especially those that are expensive to develop in fields like high technology, medicine, defense and agriculture.

Nation-State adversaries are able to mount complex operations to circumvent multiple layers of protection due to being well-funded and they can evolve tactics more quickly than most organizations can fortify their security, detection and response posture. The sheer amount of effort to infiltrate one of the Sunburst victim firms (e.g., FireEye, DoD, Big 4 Accounting, etc.) is a telling sign that this was not a mere criminal attack. The primary aim appears to be espionage because there are no known critical infrastructure services disrupted or taken offline completely.

US Government Preparedness

Although the evidence points to a Nation-State attack, which country is not clear-cut because not all victims are known; this information can help narrow the attacker’s objectives. What is clear, instead of taking on the US defense mechanisms head-on, the attackers neutralized defenses (e.g., US Cyber Command’s Defend Forward Strategy, DHS’ Einstein and CDM, etc.) through tactical deception. They blended in within a trusted environment (of a known vendor product), employing the key elements of guerrilla and asymmetric warfare: surprise ambush, covert systemic warfare, avoiding open battle, executing indirect operations and creating disorganization (especially in the backdrop of the whole of government, private industry and media preoccupied with 2020 election security in the middle of a global pandemic).

The U.S. government’s multibillion-dollar detection system, Einstein, was conceived to detect threats of this nature but was neither designed nor built to provide the necessary functionality. A 2018 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report recommended CISA to enhance Einstein to “identify any anomalies that may indicate a cybersecurity compromise” but this capability is not yet available. The report also noted that of the 23 federal agencies surveyed, 5 “were not monitoring inbound or outbound direct connections to outside entities,” 11 “were not persistently monitoring inbound encrypted traffic,” and 8 “were not persistently monitoring outbound encrypted traffic.” An irregular approach to cybersecurity across the federal government is less likely to deter attackers.

Per the known timeline of this malware campaign, adversaries have had access to a number of sensitive networks for six to fifteen months, possibly longer. Not only could sensitive data been exfiltrated but it is entirely possible the attackers planted an enormous amount of false data in intel systems, which can lead to decisions being made using misleading or false information. The true damage may take years to assess and remediate.

In the wake of the attack, the US Department of Justice’s (DoJ) Office of the Chief Information Officer (OCIO) issued a public statement acknowledging, “On Dec. 24, 2020, the DOJ OCIO learned of previously unknown malicious activity linked to the global SolarWinds incident. This activity involved access to the Department’s Microsoft O365 email environment. At this point, the number of potentially accessed O365 mailboxes appears limited to around 3-percent and we have no indication that any classified systems were impacted. As part of the ongoing technical analysis, the Department has determined that the activity constitutes a major incident and is taking the steps consistent with that determination.” The Justice Department employs over 115,000 people, which translates to around 3450 potentially breached mailboxes.

Legal Fallout

On December 7, 2020, six days before the news of the breach became public; SolarWinds announced their CEO of 11 years was resigning. Also on the same day, Silver Lake sold $158 million shares of SolarWinds and Thomas Bravo sold $128 million shares. Together, the two investment firms own 70 percent of SolarWinds and control six of the company’s board seats, giving the firms access to key information and making their stock trades subject to federal rules around financial disclosures. In a joint statement, representatives from both firms state they, “were not aware of this potential cyberattack at SolarWinds prior to entering into” the sale. A possible insider trading investigation is likely with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Soon after the discovery, a shareholder filed a class action lawsuit against SolarWinds, its CEO & President, and CFO. The suit claims the executives signed off on a series of 10-K and 10-Q SEC filings in Q4 2020 that contained information that, in violation of federal securities laws, misled stockholders to believe the company’s products were secure, which resulted in the stock price being artificially inflated.

The lawsuit alleges that the company failed to reveal in its SEC reports that:

- Monitoring products had a vulnerability that allowed hackers to compromise the server upon which the products ran;

- SolarWinds’ update server had an easily accessible password of ‘solarwinds123’ (a previously noted gap that resurfaced with the latest attack);

- SolarWinds’ customers, as a result, would be vulnerable to hacking;

- The security flaws would cause the company to suffer significant reputational harm.

SolarWinds’ external audit firm, PWC, issued an unqualified opinion in February 2020 on the annual audited financial statement. In other words, PWC indicates it was satisfied with SolarWinds’ internal control risk environment and the completeness and accuracy of financial reporting. This conclusion would not alert shareholders of any serious enterprise risks or poor information security practices.

Even companies that simply use SolarWinds’ products, and those companies several degrees removed from SolarWinds, like Microsoft or CrowdStrike, could be ensnared in a lawsuit.

In the immediate aftermath of the disclosure, researchers noted the number of SolarWinds Orion servers exposed on the web rose from a low of 1,200 on December 28, 2020 to 1,550 on January 4, 2021 (see image below).

Image Source: Censys

One possible explanation is that in the scramble to update their SolarWinds software, IT teams have misconfigured their servers, firewall rules or ports causing the servers to be visible to anyone on the Web. Thus far, state attorneys general remain quiet.

Opportunists Strike

Amongst the confirmed cybersecurity targets are Qualys, a $5 billion market cap company on the NASDAQ, CrowdStrike, Mimecast, Malwarebytes, Fidelis and Palo Alto Networks. Other known victims include Intel, NVidia, Deloitte, PWC, Lockheed Martin, Microsoft, the US Department of Energy and the Treasury.

Microsoft stated in a blog post regarding the Sunburst attack, “We detected unusual activity with a small number of internal accounts and upon review, we discovered one account had been used to view source code in a number of source code repositories. The account did not have permissions to modify any code or engineering systems and our investigation further confirmed no changes were made. These accounts were investigated and remediated,” and concluding, “viewing source code isn’t tied to elevation of risk.” Even if there is no increase in risk, access to Microsoft source code speeds an attacker’s ‘time to market’ with an exploit. A completely new class of vulnerabilities can now be quickly built because the labor-intensive nature of vulnerability reconnaissince has just been reduced.

Not even a month after the attack’s public disclosure, a solarleaks[.]net website was launched and claimed to have stolen data and source code from Microsoft, Cisco, FireEye and SolarWinds. The website listed Microsoft’s source code and repositories for $600,000, SolarWinds’ source code and customer data for $250,000, and FireEye’s red team tools for $50,000.

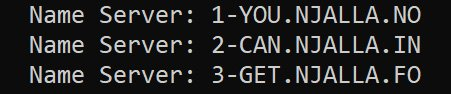

A glance at the WHOIS record for solarleaks[.]net revealed server names with the brazen message: “You Can Get No Info”.

Image Source: BleepingComputer

A copycat site, SolarLeak[.]net, listed the exact same content for sale but listed the account to send payment to having a different Monero address.

Conclusion

SolarWinds almost tripled annual profit margins from $152 million in 2010 to $453 million in 2019, with the Orion product accounting for 45% of the company’s total revenue. In the pursuit of lower costs and profitable exit multiples however, entire swaths of industries were exposed to a possible foreign adversary. Although security measures at the company were lackluster, the root cause of the supply-chain attack could be pointed to how the business was structured.

PE firms are generally profit-focused and can help underperforming businesses fulfill their potential. However, if cost-cutting measures are determined as the path to a lucrative exit then that could result in debilitating effects. PE owned software is present in almost every category, from devops automation, municipal financial management, electronic medical records, hospital software, healthcare billing, to communications. These are all points of failure for key industries and the macro economy. Just the loss of personally identifiable information (PII) from inadequate security can negatively affect the lives of ordinary citizens. Some PE owned software-based businesses are publicly traded, which triggers Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) and other regulatory oversight. On the other hand, some remain privately held and/or foreign-based with no regulations to oblige. For these firms there should be greater regulatory scrutiny and due diligence prior to approving their M&A transactions.

Cybersecurity companies (including hardware manufacturers (e.g., HPE, Dell, Huawei), AV platforms, vulnerability scanning tools, CMDBs and network monitoring platforms) serve as a bedrock of enterprise security for companies that leverage IT to conduct business. They provide foundational levels of protection that ensure the safety and security of people, businesses and nations. They also provide a portfolio view into enterprises. These vendors should be categorized as critical infrastructure, no different from power plants, clean water transports and nuclear facilities. Otherwise, they themselves become backdoors into the critical infrastructure.

When evaluating supply chain risk management, organizations should consider if their vendor is PE owned and if so, what attributes exist to provide confidence in the seriousness in which the PE firm takes cybersecurity within their overall portfolio. Organizations should identify critical suppliers that ‘touch’ their network and perform greater due diligence on their security posture.

Finally, digital forensic has much further to mature, sophisticated attackers can cover their tracks in a way to make it appear somebody else is the originator, and we may never reach 100% deterrence for evolving threats. Henceforth, industry and regulators should focus on building a platform for vulnerability mitigation. A mechanism should be setup whereby government, businesses, victims and potential targets can freely share threat intelligence and best practices without fear of retribution.

Advanced Cyber Security Metrics

The SolarWinds actors have been inside networks from six months to fifteen months. Audit and DNS logs may not even be on file since they are oftentimes overwritten within a few months. Many companies already had blind spots in their cyber programs prior to this attack, the Sunburst campaign simply adds to the complexity.

Our advanced cyber metrics offers a solution to address these gaps.

Technical Analysis

The sophisticated actor(s) showcased a broad range of operational security (OpSec) techniques, camouflage tactics, and anti-forensic behaviors to reduce the likelihood of detection.

The complex attack, referred to as “the SolarWinds event,” “SUNBURST,” or “Solorigate,” was first discovered by top-tier cybersecurity firm FireEye, which traced the account of a new device enrolled on its Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) solution (defaulted to trigger an alert) originating from its trojanized Orion software.

The initial attack vector into SolarWinds was through a misconfigured workflow software that developers typically use in the Continuous Integration (CI) toolchain. These applications oftentimes hold developer accounts, passwords and other authentication components, which if compromised, enable stealth exploitation of source files. We can summarize the attack as having 4 distinct stages:

Stage 1 – Embed Then Hibernate

The SolarWinds attackers placed their malware, called SUNSPOT, into the software CI build system, which then quietly inserted the SUNBURST backdoor into the Orion code every time the developers compiled it.

Safeguards were added to SUNSPOT to avoid the Orion builds from failing and potentially alerting developers. For example, the malicious actors developed the code using the same coding style of the build system and Orion to prevent detection. They also included a hash verification check whenever SUNSPOT replaced a source code file (e.g., InventoryManager.cs) at the time MsBuild.exe processes were running. This ensured the injected backdoor code was compatible with a known source .cs file to avoid triggering any errors.

After the attacker(s) carefully signed their malware into the Orion software and sent it out from a trusted source (SolarWinds), the trojanized update set a delay time of up to 14 days before execution into Stage 2. In other words, no malicious activity will begin until the 14-day period has elapsed, likely to avoid detection in audit logs since many organizations purge security logs after seven days (to minimize storage costs and to make searching them easier).

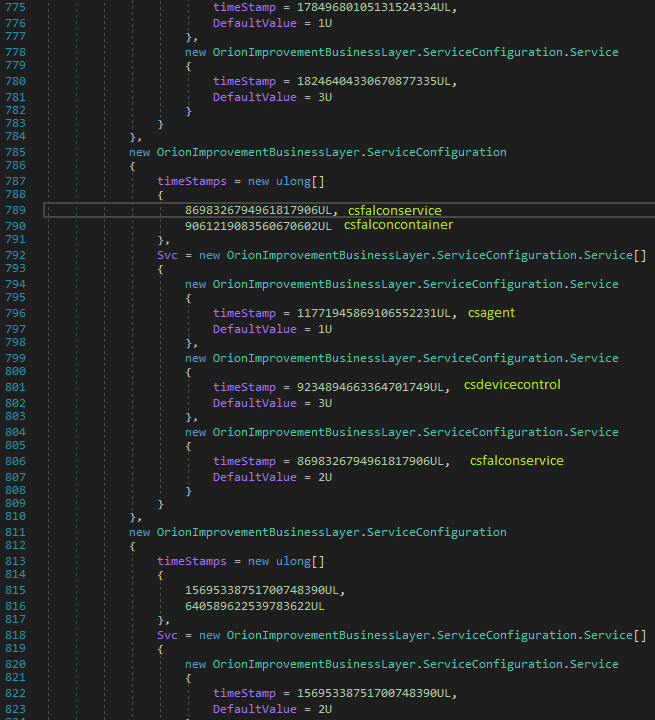

After the dormant period expires, the program quickly disables security software, such as CrowdStrike, Carbon Black, ESET, F-Secure, and Microsoft Defender. The image below depicts the program disabling CrowStrike. Here the malware code checks if the CrowdStrike processes csfalconservice or csfalconcontainer are running, if so, it disables the csagent, csfalconservice, and csdevicecontrol services by modifying its service registry entry.

Image source: Symantec

Other attributes of the SUNBURST program are designed to avoid running if security systems are detected (e.g., Tanium, Kaspersky, Panda, AVG/AVAST, CyberArk, Symantec, Dell SecureWorks, Bromium, LogRythm, Raytheon Cyber Solutions, etc.), and possibly avoid running on systems not of interest to the attackers.

Stage 2 – Reconnaissance

Once in via the tainted update, the sophisticated adversaries could use their newfound privileges on victim systems to take control of certificates and keys used to generate system authentication tokens, known as SAML tokens, for access to cloud assets like Microsoft 365 and Azure. Organizations manage this authentication infrastructure locally, rather than in the cloud, through a Microsoft component called Active Directory Federation Services (ADFS).

Once an attacker has the network privileges to manipulate this authentication scheme, they can generate legitimate tokens to access any of the organization’s Microsoft 365 and Azure accounts, without requiring passwords or MFA. From there, the attackers can create new accounts and grant themselves the high privileges needed to roam freely without raising red flags.

An excerpt from FireEye’s January 2021 report, describes the four primary techniques it had seen the attackers utilize to laterally move to Microsoft 365 cloud:

- Steal the ADFS token-signing certificate and use it to forge tokens for arbitrary users (sometimes described as Golden SAML). This allows the attacker to authenticate into a federated resource provider (such as Microsoft 365) as any user, without the need for that user’s password or their corresponding MFA mechanism.

- Modify or add trusted domains in Azure AD to add a new federated Identity Provider (IdP) that the attacker controls. This allows the attacker to forge tokens for arbitrary users and has been described as an Azure ADbackdoor.

- Compromise the credentials of on-premises user accounts that are synchronized to Microsoft 365 that have high privileged directory roles, such as Global Administrator or Application Administrator.

- Backdoor an existing Microsoft 365 application by adding a new application or service principal credential in order to use the legitimate permissions assigned to the application, such as the ability to read email, send email as an arbitrary user, access user calendars, etc.

In this second stage, a backdoor opens to encode the internal Active Directory domain name and installs security products into domain name system (DNS) requests. The malware renames tools and binaries and puts them in folders that look like files and programs already present on a machine. It prepares special firewall rules to minimize outgoing packets for certain protocols and then removes the rules after completing reconnaissance.

Interestingly, the backdoor does not accept any commands from the command & control (C2) server. An estimated 99.5% of the installed SUNBURST backdoors never progress into Stage 3.

Stage 3 – Beacon Out

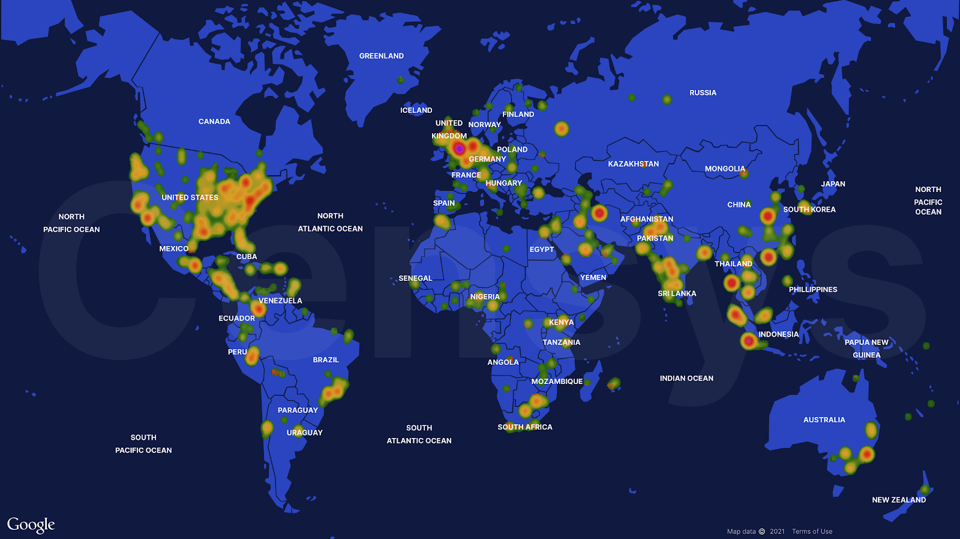

In Stage 3, the SUBURST backdoor begins sending DNS queries for seemingly random subdomains of avsvmcloud.com. Some of the DNS queries actually contain the victim’s internal AD domain encoded into the subdomain. To minimize suspicion, attackers communicate through IP addresses in the United States rather than a foreign country. Only 23 victims appear to have been targeted in Stage 3 as of January 2021.

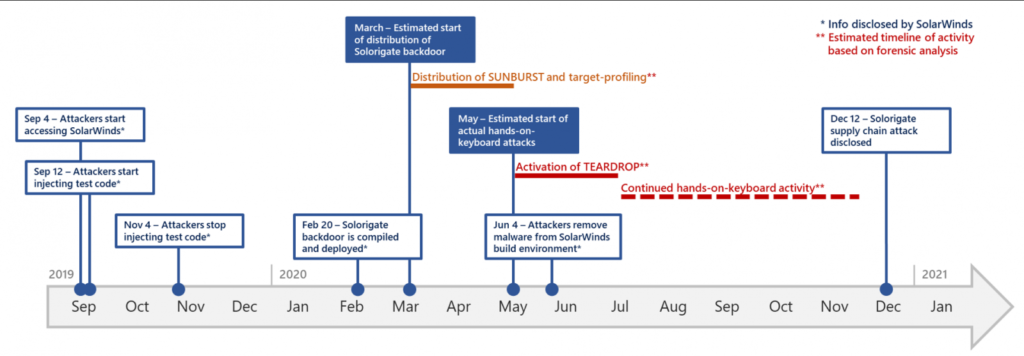

It turns out Sunspot was deployed in October 2019; indicating the attacker(s) tested out their code before operationalizing it in 2020. The timeline below shows the backdoor deployed in February 2020 and compromised networks in March 2020. SolarWinds disclosed that the attackers removed the Sunburst backdoor from SolarWinds’ software build environment in June 2020 after being distributed broadly to Orion customers in March, indicating the sophisticated actors had reached a sufficient number of interesting targets and their objectives then shifted from deployment to manual lateral movement to view/exfiltrate data. A fourth malware variant, called Teardrop, is delivered directly by the initial Sunburst backdoor but appears to require manual initiation.

Image Source: Microsoft via Bleeping Computer

Stage 4 – Exfiltrate Data

In the 4th Stage, the C2 server responds to an HTTPS communication to allow the attacker to bore deeper into the victim’s network via manual lateral movement. This is possible because event logging is disabled, new firewall rules minimize outgoing packets for certain protocols, and security services are turned-off.

More specifically, attacker(s) receive encrypted data broken into multiple variable sized chunks. The size of each chunk is randomly determined. For example, a small size generates a random chunk of data between 16 and 28 bytes whereas greater bytes are grouped together for a larger size. On receipt, the attacker(s) will decode and concatenate all of the message chunks, skipping junk chunks where the timestamp is deliberately not set.

Because multiple DNS requests will have to be made to transmit all payload information, the attackers require a unique ID to know which computer the information is coming from. DNS is a distributed protocol, meaning the infected computer does not contact the attacker’s C2 server directly, but instead the DNS request is passed through multiple intermediaries before reaching the attacker’s DNS server. Only by including a unique user ID for each infected computer within the DNS request are the attackers able to combine the multiple requests.

What Mitigation Steps Can You Take?

While SUNBURST has demonstrated a high level of sophistication and evasiveness, and although organizations should brace for a surge in these methods from other attackers, the observed techniques are both detectable and defensible.

Asset Management

One of the biggest hurdles is simply finding all of the SolarWinds Orion installations, and what versions they are actually running. Fixing basic asset management hygiene, and mapping and inventorying all network and VLANs (via IP Address Mapping – IPAM) is a foundation of a thoughtfully designed security program. Review your asset inventory or configuration management database (CMDB) if you have SolarWinds Orion installed. If a complete asset inventory is not available, review management servers for SolarWinds Orion installations.

Access and Configuration

The SolarWinds attackers pivoted their local access to infiltrate their victims’ Microsoft 365 email services and Microsoft Azure Cloud infrastructure —a treasure trove of potentially sensitive and valuable data and the latter offering root access to API keys (which allows full access). The challenge of preventing these types of intrusions into Microsoft 365, Azure and even Amazon Web Services (AWS) is that they don’t depend on specific vulnerabilities that can simply be patched. Instead, attackers use an initial attack that positions them to manipulate the cloud in a way that appears legitimate.

To mitigate the risk of compromised cloud accounts, rotate credentials, institute least privilege protocols, and deploy Orion on standalone accounts isolated from all other cloud-based resources. For example,

- Perform a manual review of each identity and resource to determine the extent of exposure and implement least privilege.

- To prevent the takeover of databases storing Azure and AWS API keys, rotate the credentials in the Orion database under the assumption all have been compromised.

- Orion requires access to an Identity and Access Management (IAM) identity that it will be monitoring and managing. Restrict privileges of the IAM identity to the absolute minimum and enable alerting on high-risk activities. If the use of Orion is suspended, remove that identity altogether or, at the very least, revoke its privileges.

- Ensure proper configuration of the server that holds token signing certificates and minimize write access to it to the minimum.

- Monitor tokens to identify any that were issued months or years ago suddenly being employed to authenticate activity. This will require adequate logs to indicate when a token was issued.

- Monitor accounts for any unexpected user authentication and lateral movement between key assets, such as the domain controllers and email servers.

Indicators of Behavior (IOB)

IOB is another defense-in-depth approach that can be used to determine if there’s been a compromise. This can include reviewing DNS (as well as firewall and web proxy) records:

- for a query to *.avsvmcloud.com that points to an IP address in any of the following three networks that are known to be tied to the attacker(s): 18.130.0.0/16, 99.79.0.0/16 or 184.72.0.0/15;

- for a query to *.avsvmcloud.com that returns a CNAME record

- for any backdoor DLL present on systems, host memory or disk

- for HTTPS communication to any of the other known SUNBURST C2 domains:

- avsvmcloud[.]com

- databasegalore[.]com

- deftsecurity[.]com

- digitalcollege[.]org

- freescanonline[.]com

- globalnetworkissues[.]com

- highdatabase[.]com

- incomeupdate[.]com

- kubecloud[.]com

- lcomputers[.]com

- mobilnweb[.]com

- panhardware[.]com

- seobundlekit[.]com

- solartrackingsystem[.]net

- thedoccloud[.]com

- virtualwebdata[.]com

- webcodez[.]com

- websitetheme[.]com

- zupertech[.]com

If an IOB is seen and the affected server is a physical machine, disconnect it from the network, but leave it running (if it is a virtual machine, pause it). This will preserve valuable data for incident analysis, forensics and response.

In addition to the above strategies, please review guidance from the US CISA and FireEye.

In 2017, the federal government was ordered to remove from its networks software from a Russian company, Kaspersky Lab, which was deemed too risky. It took over a year to get it off the networks. Even if organizations double that pace with SolarWinds software, and even if it wasn’t already too late, the situation could remain dire for a long time.